Originally posted here on NPR.org

Missy Hart grew up in Redwood City, Calif. — in gangs, on the street, in the foster care system and in institutions.

“Where I’m from,” the 26-year-old says, “you’re constantly in alert mode, like fight or flight.”

But at age 13, when she was incarcerated in juvenile hall for using marijuana, she found herself closing her eyes and letting her guard down in a room full of rival gang members.

Back then, she says, yoga was just another mandatory activity, run by a Bay Area program called The Art of Yoga Project. It offers what it calls “trauma-sensitive yoga” to incarcerated girls.

At first, 13-year-old Hart felt uncomfortable. But, gradually, she learned to use the poses and breathing to relax, and she loved it.

“Most of us [in juvenile hall] come from traumatic childhoods,” she says. “It was the only time you experienced a quiet time, when everything was so chaotic.” She believes the practice helped her cope with symptoms of bipolar disorder.

A new report from the Center on Poverty and Inequality at Georgetown University’s law school, says that for young women like Hart, who have been through trauma, there is mounting evidence that yoga can have specific benefits.

The study focuses on girls in the juvenile justice system. It also reviews more than 40 published studies on the mental health benefits of yoga.

“What we’re learning,” says Rebecca Epstein, one of the report’s authors, “is that fights go down on wards after adolescents participate,” in yoga.

Girls, she adds, “are requesting medicine less often. They have fewer physical complaints.”

The findings, Esptein explains, come from speaking to experts in the field, as well as the authors of peer-reviewed articles and some randomized, controlled trials.

Two Georgetown pilot studies showed girls and young women who did yoga reported better self-esteem and developed skills that they could use in stressful situations — taking care of their own children, for example.

Educators and others who work with youth are, increasingly, paying attention to the science of trauma.

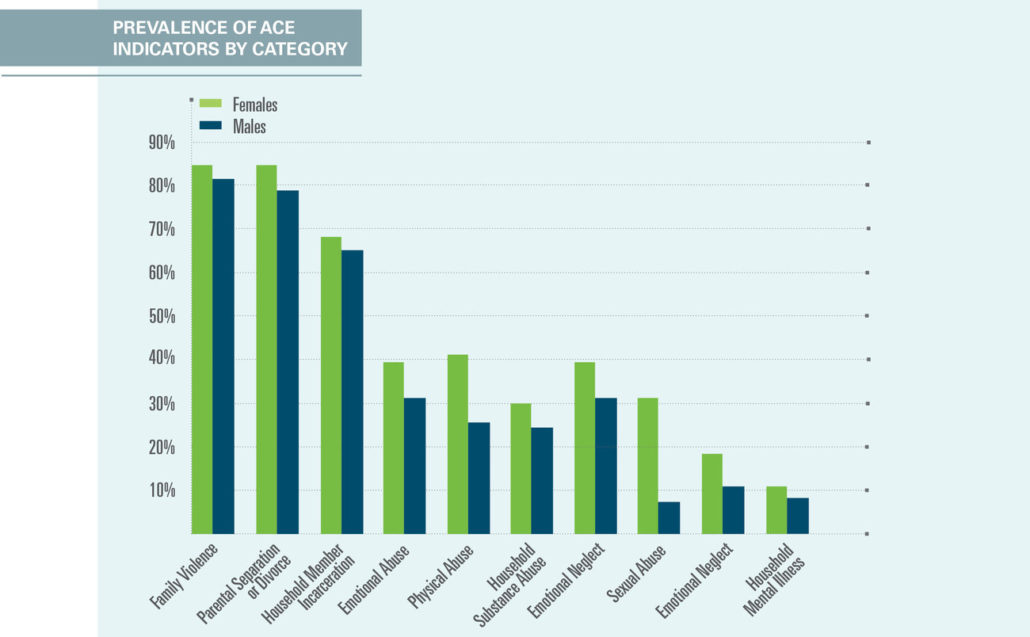

Large studies show that people who have been through one or more “adverse childhood experiences” have not only poor mental health outcomes, but also higher incidence of heart disease, diabetes and even some cancers. Those experiences might include such things as physical abuse, the incarceration of a close family member or mental illness in their household.

Further, statistics show that compared with boys, girls experience different forms of childhood trauma, with an impact that adds up over time. They disproportionately experience sexual violations, for example. And, for girls, this abuse is more likely to occur in the context of a relationship, Epstein says, which interferes with forming intimate and trusting relationships with others.

The new Georgetown Law report argues that, since the effects of trauma can be physical, “body-mind” interventions, like yoga, may be able to uniquely address them. Regulated breathing, for example, calms the parasympathetic nervous system. Practicing staying in the moment counteracts some of the dissociative effects of trauma. And the physical activity of yoga, of course, can directly improve health.

Yoga that is specifically designed for victims of trauma has modifications when compared with traditional yoga teaching.

For example, says Missy Hart, “they always ask you if you want to be touched,” for an adjustment in a pose. “I see now that really helped me. Other girls who have experienced sexual abuse, sexual trauma or are in there for prostitution at the age of 13, 14, they had their body image all mixed up.”

And the institution doesn’t always help, she says.

“Being asked to be touched, it gave us a little power back in a place where all our power is taken,” she explained. “We’re kids and we’re being strip-searched. We can’t even go to the bathroom, take a shower, or brush our teeth without asking.”

Yoga, she said, offered choices. “You can sit and reflect and think about what you want to think about. It helped us feel normal.”

When Hart turned 18, she was out of the foster care system, and became homeless for a time. “I was really searching for myself.”

Today, she is painting and studying to become an art therapist at Foothill College, near San Jose, Calif. She’s going back this summer to one of the institutions where she spent time as a girl, this time as an art teacher.

And, she is beginning her vinyasa yoga teacher training certification. Her ultimate goal, she says, is to open a group home that will offer creative arts and yoga. “When I was doing yoga, that seed was planted. I built my toolbox.”